What Causes Sciatic Pain?

How Can Genes Help to Understand Sciatica?

Stretches for Pain Relief

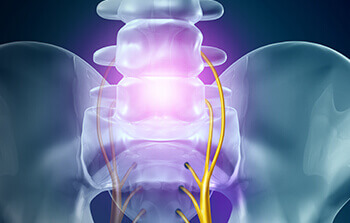

The sciatic nerve is the longest nerve in the body, stretching across the lower back, spreading from the hips to the buttocks and down the legs. Sciatica is a condition referring to pain radiating along the path of the sciatic nerve and can range from mild, to chronic and debilitating.

The lifetime incidence of lower back pain 1 is estimated to be between 58-84%, suggesting that most people are likely to experience this type of nerve pain at some point in their lives.

The exact prevalence of sciatica is variable in the literature, due to a lack of agreed definition of thedisorder in epidemiological research 2 . Sciatica causes significant costs 3 for healthcare services as well as independent businesses due to workplace absenteeism.

Understanding the cause, trajectory and genetic heritability of sciatica is essential for empowering people to take preventative measures and practise self-care from the comfort of their own homes.

Genetic research is making powerful strides in helping us to understand risk factors which may aggravate sciatic pain and enable targeted treatment and self-help techniques.

The following article aims to discuss the diagnosis and cause of sciatica as well as reveal some exciting discoveries in the field of biogenetics and DNA testing which may help you to find ways to reduce the burden.

How Do I Know If My Pain is Sciatica?

In the absence of an agreed consensus on definition, there is also a lack of ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing sciatica. Symptoms are likely to vary. For example, approximately two thirds of those reporting lower back pain also report pain in the legs 4 .

Leg pain can also be indicative of more severe root nerve disorders and so, requires further investigation using a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan to identify the cause. Other neurological symptoms may include weakness and numbness of the legs.

It has been argued that the severity of such symptoms should be routinely considered as part of the assessment of sciatica to help determine the course of treatment, however, diagnostic overlap between nerve conditions causes significant debate 5 .

Scientists have made efforts to standardize the way sciatica is assessed to encompass the variability in symptoms whilst also ensuring an accurate diagnosis, however, this has proved no easy task.

Using an MRI scan to diagnose sciatica is in many medical circles considered controversial, as studies have shown it can lead to the incorrect classification of nerve pain in certain clinical settings 6 .

There has subsequently been some effort in recent years to develop an assessment framework 7 for sciatica based on clinical symptoms such as severity and onset, which can be used in primary care i.e. at the GP.

Using a set of questions to diagnose sciatica, however, has its own problems. Trying to distinguish between similar nerve disorders on the basis of self-report is not a reliable method of diagnosis either.

Onset of sciatica may be sudden but can also be gradual over time. Risk factors include age (peaking at 45-64 years), height, smoking and general life stress, however, regular strenuous action and activities which involve vibration of the whole body e.g. driving, can also induce symptoms 8 .

Asking the right questions and monitoring risk factors is important for catching onset of sciatica early; before it becomes debilitating. The research suggests that it is best, however, to look at risk populations (on the basis of genetic factors) rather than risk factors 9 .

Overall if you’re feeling confused about what is classed as sciatica, you’re about on par with the rest of the scientific community! It may be helpful to delve a little bit deeper to help understand what may cause root nerve pain, and why it may be more severe for some more than others.

What Causes Sciatic Pain?

It is estimated that 85% of diagnosed sciatica cases are associated with disk disorder 10 ; specifically, up to 90% are caused by a herniated disc with nerve root compression 11 .

A number of case studies citing ‘rare’ alternative causes of sciatica are present in the literature, including the discovery of a discal cyst 12 or tumour 13 causing nerve compression.

These cases are rare enough to have a scientific paper written specifically for them, so there is no need to panic. For most people, however, sciatic pain is likely to be caused by chronic strain or injury; common occurrences of everyday life.

Understanding factors which may worsen symptoms of sciatica has also been the subject of clinical research. Strenuous physical activity has been shown to correlate with the onset of sciatic pain whereas psychosocial factors such as stress have been linked to persistence of symptoms 14 .

It has also been proposed that an abnormal immune response may mediate the severity of pain 15 . It’s not just working a physical job that can give you a bad back; feeling stressed and unhappy can also inflame symptoms and keep you in pain for longer!

How Can Genes Help to Understand Sciatica?

Sciatica is reported to have a high heritability, meaning that a large proportion of variance in characteristics can be attributed to genes. The genetic mechanisms, however, are poorly understood. Despite evidence to suggest a genetic vulnerability, unfortunately, research of this nature is rarely replicable, and in essence, no one can quite work out what is causing the measured effect 16 .

All is not lost for biogenetics, however, as there are other ways the study of DNA has improved our understanding of sciatica.

A study of inflammatory biomarkers and their relationship to the clinical symptoms of sciatica found that there may be some relationship between genes and the severity of sciatic pain 17 . Similarly, in a study investigating mediating factors in recovery from lumbar radicular pain (along the path of the sciatic nerve), genetic biomarkers were found to predict speed of recovery 18 .

It may be an unfortunate truth, therefore, that some people are simply more genetically prone to a higher severity of pain, or perhaps a lower pain threshold. This revelation brings us closer, however, to understanding why some people find sciatic pain more debilitating than others.

Genetic research has made significant advances in the treatment of several musculoskeletal disorders, however, the ambiguity around the definition of sciatica makes applying similar genetic methods to treatment hard.

The development of gene therapy; a novel treatment which uses proteins produced as a result of gene transfer to help reduce inflammation and aid repair in conditions requiring cartilage reparation 19 e.g. osteoporosis, has been ground-breaking.

That being said, nerve-growth factor; a gene providing instructions for producing proteins (antibodies) at a neural level, has been trialled as an analgesic for lower back pain 20 . This works by fighting the auto-immune response which causes flare up of nerve pain.

Although found to be effective in many cases, clinical trials were stopped in 2010 after subjects suffered rapid joint destruction leading to joint replacement as a result of the treatment. Although clinical trials are now underway again, such treatments should be viewed with caution until the mechanisms are better understood 21 .

Research has also found a genetic component to Intervertebral disc disease (IDD) which is characterised by inflammation of the sciatic nerve 22 , so, there is a good chance that the inflammation process at least, can be predicted by genetic research.

Genetic advances have led to alternative treatment for neuropathic pain by informing the regulation of inflammatory mediators 23 . Such research has also informed the development of analgesic medication, again targeting inflammation of the sciatic nerve and alleviating symptoms to much success 24 25 .

Where medical science has failed to agree upon a consensus on how to routinely diagnose and treat sciatica, biogenetics appear to have moved things forward.

Medicines and therapeutic interventions which target inflammatory processes are likely to be most effective; however, different courses of treatment will suit different people.

Assessing psychosocial factors in combination with levels of physical activity has been shown to be the most effective way of tailoring treatment 26 for musculoskeletal conditions. Combining treatments 27 such as physiotherapy, physical exercise, surgery and analgesic medication has been shown to be most effective in treating lower back pain.

In fact, there is strong support for multi-modal analgesia 28 for all pain management after surgery[28]. Exploring the genetic components of physical activity and the impact this may have on the management of lower back pain is also the subject of research to enable your GP to prescribe more tailored treatments to give better results.

Stretches for Pain Relief

Managing the burden of sciatica (or generalised lower back pain) requires significant changes to the way we think about our health. Health services have traditionally operated using an ‘illness model’ i.e. treating symptoms/pain in isolation on a case-by-case basis, rather than trying to prevent and manage the cause of illness (stopping people from becoming unwell in the first place).

In the UK, the treatment of musculoskeletal health is moving towards an integrated model of care 29 which involves preventative and rehabilitative measures such as changes to lifestyle and interventions to reduce stress in the workplace 30 .

This is an essential movement toward empowering people to care for their musculoskeletal health from home; increasing independence and reducing the need for healthcare intervention. There is evidence to suggest that a patient’s expectation of treatment 31 from primary care has a positive or negative impact (corresponding with a positive or negative expectation) on treatment outcome[31].

This means that healthcare services need to up their game in terms of promoting the value of self-management to patients who may be unsure, to significantly improve the likelihood of a good outcome.

Scientists have recently been investigating self-management techniques for musculoskeletal conditions such as sciatica; trialling new therapeutic interventions and technologies.

This has included improving the effectiveness of smartphone apps for the management of lower back pain 32 and exploring the impact of educational leaflets given to people when they attend their GP 33 .

Non-traditional interventions such as acupuncture have also been found to be effective 34 , however, exercise programs retain strong support as the most effective way to manage pain outside of a primary care setting. That being said, adherence to self-care treatment 35 programmes is poorly measured[35] so the modest success rates reported are likely to be even more successful than first thought.

One study found that most people diagnosed with acute sciatica and awaiting surgery, benefited from a bespoke course of physiotherapy to help manage pain and discomfort 36 .

Another study found that prescribed exercise was superior to advice to stay active for reducing sciatic leg pain 37 , however, advice to stay active has been found to be superior to bed rest 38 .

The consensus, therefore, is that sciatic pain can be managed effectively at home using several recognised exercises and stretches, as approved by physiotherapists.

Yoga is a recognised form of stretching exercise which has been found to be effective for the self-management of sciatica and generalised lower back pain 39 .

Numerous studies have found yoga to be effective for relieving pain and improving functional ability 40 41 , as well as improving overall quality of life 42 . Yoga exercises can be simple and easy to incorporate into everyday life.

In fact, genetic research has discovered the mechanism which makes yoga particularly beneficial for managing sciatica pain. Practising regular yoga has been found to downregulate inflammatory biomarkers meaning that it reduces inflammation of the central nervous system 43 .

The use of yoga stretches has subsequently been recommended for several chronic conditions 44 . DNA testing can help to understand age related health risks and offer a full assessment of bone, muscular and metabolic health.

A DNA Wellness Report can help you work out the best way to manage conditions such as sciatica and find an exercise program which works for you. To explore optimum movement and recovery, it may be helpful to have your DNA assessed by sports and mobility experts.

They will provide you with a bespoke report which offers insights into your body’s strengths and weaknesses as well as expert advice regarding how to look after your body including recovery from injury.

Sciatica is a debilitating condition which is all too common in the modern world. In the absence of a gold standard for diagnosis and treatment, what we do know is that the way we think about our musculoskeletal health needs to change if we are to reduce the expensive burden on healthcare services and reduce the everyday pain felt by an increasingly large number of people.

Genetic research has shown that inflammatory biomarkers play a key role in mediating the severity of pain felt by those with sciatica, and therefore, interventions should focus on reducing inflammation.

Yoga is the most recent revelation for deregulating biomarkers and empowering people to manage their pain from home. Time to dig out your yoga mat and practise your sun salutation to improve wellbeing and start living pain-free!